While there’s plenty of real-time golf to take in at the 122nd U.S. Open this week, fans and spectators won’t be want to miss the on-site “Hard-Earned Glory” museum exhibit, a fan experience that showcases key golfers who broke down barriers in the game.

Located near fan services by the Gate 6 entrance and along the second fairway, the exhibit is a collaboration between the The Country Club, USGA® and Town of Brookline designed to tell the story of the sport alongside major American cultural milestones, with an emphasis on underrepresented groups.

“There’s a ton of history here at The Country Club, not only [Francis] Ouimet, and we tell that story a lot,” said USGA Golf Museum and Library Director Hilary Coe Cronheim, “but we also wanted to tell the history of the U.S. Open within a broader kind of social and cultural context, featuring U.S. Open competitors, champions, qualifiers and the different physical, mental, emotional challenges that they had in competing.”

The exhibit features 50 significant artifacts from the USGA archives along with photographs and video highlights, and is part of golf’s larger campaign to celebrate and recognize diversity, equity and inclusion.

From a wall placard about the Boston dentist who first patented wooden golf tees in the 19th century to trophies awarded at this year’s inaugural U.S. Adaptive Open later this summer, these items tell the story of how the golf has advanced throughout the history of the United States.

A major element of the museum’s lineup is its artifacts from those who made golf more inclusive for people of color.

When visitors first enter the space, they’re treated to a wall placard featuring John Shippen and Dr. George Franklin Grant, two pioneers of the game. Shippen was the first African American and first American-born professional golfer to compete in the U.S. Open. As a club pro, he was tasked with making and repairing clubs for members, and one of which is on display.

Grant, meanwhile, was the first African-American faculty member at Harvard University and a practicing dentist in the Boston area. A recreational golfer who grew tired of teeing the ball on a mount of wet sand, Grant patented the first wooden golf tee in December 1899, and it’s been an integral part of golfers for more than a century.

One item that Cronheim called attention to was a head cover embroidered with the number 42 that was owned by Jackie Robinson.

“Jackie Robinson didn’t play a U.S. Open, but he had a tremendous impact using his celebrity and his platform to break down those racial barriers,” Cronheim said.

A recent acquisition of the USGA Museum on display is the glove Charlie Sifford wore at the 1967 Hartford Open when he became the first African American to win on the PGA Tour.

Cronheim also pointed out head covers owned by Althea Gibson, the first African American woman to play on the LPGA Tour, meant to pay tribute to her accomplishments in both golf and tennis as a multi-sport athlete.

The museum features artifacts specific to women who made noteworthy achievements in the sport, such as a champion’s medal from Glenna Collett-Vare. Collett-Vare, a member of the Golf Hall of Fame, was widely considered the best woman golfer of her day, winning a record six titles at the U.S. Women’s Amateur Championship.

The women’s exhibits are special to the USGA team that worked on the museum, Cronheim said.

“Really anything that we do we try to integrate,” she said. “We’re a [museum] staff of all women, so we feel strongly about women’s stories.”

There’s also a wall titled “The Future Is Now”, which, in part, highlights international women such as Hall of Famers Annika Sorenstam and Se Ri Pak, who have attracted new audiences to women’s golf.

An exhibit on the far side of the museum calls attention to golfers who have advanced LGBTQIA representation within the golf community.

One featured golfer is Tadd Fujikawa, who became the first male professional golfer to come out as gay in 2018. The museum features a golf ball used by Fujikawa in the 2006 U.S. Open, when he was the youngest golfer (15) to ever qualify for the event.

Another featured item is a hat worn by Mel Reid in the 2021 U.S. Women’s Open. The hat, which features a Pride rainbow inside the insignia, is the first hat with a Pride logo worn in competition by a professional golfer.

One goal of the space is “trying to reframe some of these U.S. Open stories into what it takes to compete,” Cronheim said, which the USGA intends to do by telling them in ways they are not typically presented.

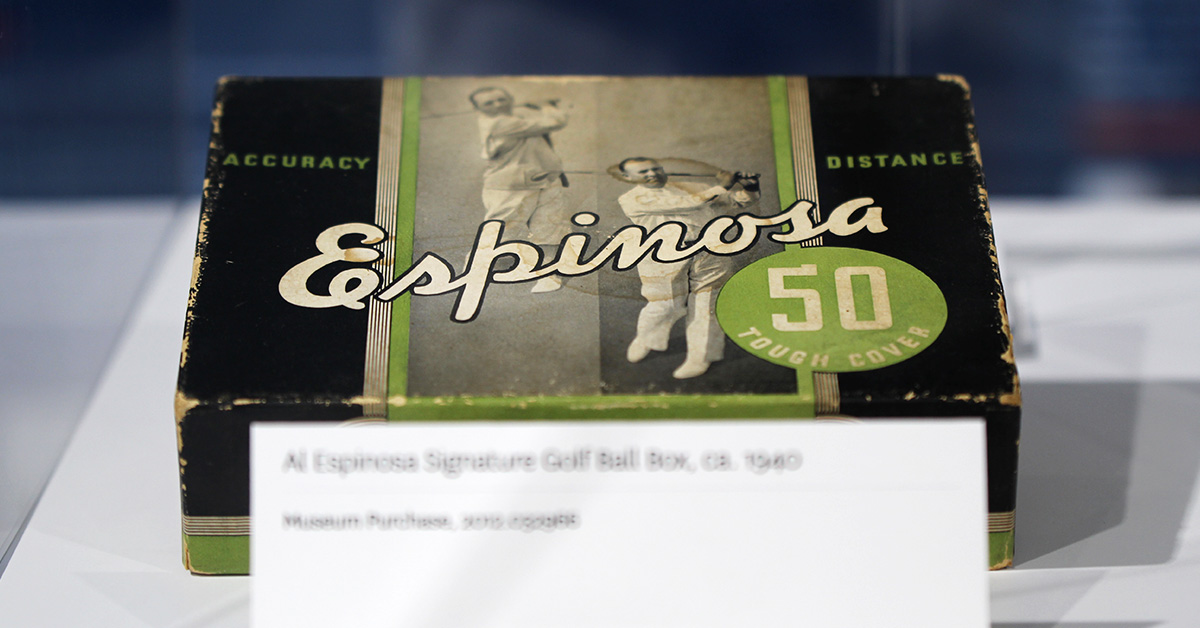

One such story is that of Al Espinosa, a Mexican-born golfer who pushed golf icon Bobby Jones to a playoff in the 1929 U.S. Open at Winged Foot in New York. Espinsoa also played on the first three U.S. Ryder Cup teams, including the inaugural one in 1927 at Worcester Country Club in Massachusetts. “Most people know about Bob Jones, but they don’t know anything about Al Espinosa,” Cronheim said.

The exhibit also describes the “tremendous intellectual pressure” of Bobby Jones, who won the Grand Slam in 1930 but also dealt openly with his mental health, another facet of the story that remains overlooked, Cronheim noted.

Visitors attending the U.S. Open can visit the museum at the far end of the second fairway at the southern end of the course, which is also located near the Gate 6 entrance. Those who cannot visit the on-site exhibit can check out separate exhibitions located at the Brookline Village Library and the Boston City Hall.

There will also be a series of programs focused on promoting job opportunities within golf, ensuring greater accessibility to the championship and celebrating diversity within the community.

Visit MassGolf.org and follow @PlayMassGolf on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for the latest content from this year’s U.S. Open Championship at The Country Club.