The significance of Black history in golf has helped shape the game in Massachusetts and beyond. Throughout February, Mass Golf will shine a spotlight on the achievements, contributions, and lasting impact of African American golfers in the state’s history.

This year’s celebration holds even greater significance as Mass Golf embarks on its 125th anniversary. As part of this commemorative year, we are committed to amplifying the rich history of golf in the Commonwealth, which includes the groups and individuals that not only demonstrated excellence on the course but also broke barriers and paved the way for future generations.

Please revisit this page throughout the month as we share new insights, archival discoveries, and inspiring stories that celebrate Black History as a part of the larger story of golf in Massachusetts.

For more than a century, William J. Devine Golf Course at Franklin Park has been a symbol of accessibility and community, and is a major part of the evolving story of public golf in U.S. The park itself came about within Frederick Law Olmsted’s design of Boston’s “Emerald Necklace,” which connected a series of public landscapes to form the city’s first park system. Golf within the park has long been cherished by Bostonians — not just early luminaries such as Francis Ouimet and Bobby Jones, but citizens of all walks of life.

The game, however, has had its checkered past in the area, even before it was formally established. When former baseball legend and sporting goods magnate George Wright tried to demo golf in 1890, he was once stopped by a beat cop who insisted he needed a permit to play. It was eventually granted, but golf in its current form didn’t take shape for several years after. By 1900, under the leadership of pro Willie Campbell and his wife Georgina, the course saw 40,000 rounds (9 holes) per year. In the 1920s, Donald J. Ross volunteered his services to expand it to 18 holes.

From there, it served the likes of Black and minority golfers such as Al Hayes, who at age 19 in 1941, moved to Boston from Florida, a state where he could caddie but not play.

However, fast forward to the early 1980s, and the course had been left in ruins, reduced to just four playable holes, its greens and fairways overtaken by neglect, strewn with litter and abandoned cars. The city, strangled by budget cuts from the 1982 Proposition 2 ½ tax cap, had virtually abandoned it.

Just as the course teetered on the edge of extinction, a group of dedicated Black golfers and community leaders refused to let it disappear. Among those leading the charge were George Lyons, a teaching pro at William J. Devine, and Archie Williams, a businessman and avid golfer. They formed the Franklin Park Golfers Association (FPGA), determined to restore the course to its former glory, guided by ideals of racial inclusion in a sport long known for its exclusivity.

They found an ally in Bob McCoy, who in 1982 became Boston’s highest-ranking Black government official when he was appointed Parks Department commissioner. McCoy, working alongside the FPGA, the Franklin Park Coalition, and other activists, spearheaded the course’s revival. He secured an irrigation project and helped push through a $1.3 million investment from Mayor Ray Flynn’s “Rebuilding Boston” program.

Still, financial support alone wasn’t enough. Lyons, Williams, and their team weren’t afraid to get their hands dirty, literally. According to Williams, the city mowed the fairways, but Williams and co. cut the greens and tees themselves. By the late 1980s, the course’s transformation was in full swing. The city enlisted Bill Flynn, the golf course owner and manager who had successfully restored George Wright Golf Course, along with course architect Phil Wogan, whose father had worked with the legendary Donald Ross. Together, they completed the full restoration of Franklin Park, and in 1989, the course officially reopened as an 18-hole public course, not just revived, but thriving.

In 1992, Tiger Woods gave a free talk and demonstration prior to playing (and winning) the 1992 U.S. Junior Amateur at Wollaston Golf Club. For over a decade, Tiger Fever swept a new generation of golfers.

But for Lyons, Williams, and the FPGA, it was never just about golf. Williams made their vision clear:

“Our goal was to make it a multi-racial, multi-gender golf course. It’s what the whole city should be like.”

They launched outreach initiatives like the Black & White on Green Tournament and youth golf programs that provided free lessons and job opportunities. Lyons understood that golf wasn’t just a game, it was an industry, a billion-dollar one, that should be accessible to everyone.

Today, Franklin Park remains a vibrant, inclusive golfing community, with groups like the Fairway Ladies of Franklin Park and the Franklin Park Men’s Inner Club carrying on the mission. A plaque on property honors the individuals whose dedication saved the course, ensuring that their fight for equal opportunities in golf would never be forgotten.

Reflecting on those efforts, Lyons said, “Full access to the game of golf didn’t, and still doesn’t, come automatically. What is realized these days is the result of efforts made by people who fought for years to open the doors of golf. There are still doors to be opened.”

On August 5, 1966, Althea Gibson made history once again — not on the tennis court, but on the golf course.

Competing in the LPGA Lady Carling Eastern Open at Pleasant Valley Country Club in Sutton, MA, the 11-time Grand Slam-winning tennis star shot a dazzling 6-under-par 68, breaking the women’s course record previously held by legendary champion Mickey Wright. Her remarkable back-nine score of 31 electrified the crowd of roughly 4,000 spectators, giving her a four-stroke lead after the first round.

Though Gibson didn’t ultimately win the tournament, the performance was a defining moment for the then-38-year-old phenom. Having dominated tennis throughout the 1950s — with landmark victories at Wimbledon, the U.S. Open, and the French Open — she had already changed the face of the sport. In 1957, she became the first Black player to win Wimbledon, and a year later, she became the first Black player to win the U.S. Open.

However, financial instability and the lack of prize money during that era led her to explore another competitive avenue: professional golf. In 1964, Gibson became the first Black woman to join the LPGA. She played in 171 tournaments over the next decade-plus, competing against some of the greatest female golfers of the time.

Her journey in the sport was far from easy. In the racially charged climate of the 1960s, she was often met with discrimination. Some tournament organizers in the South discouraged her participation, fearing controversy or backlash. Instead of protesting publicly, Gibson took a measured and dignified approach, cheerfully signed autographs, and chatted with spectators for those who did come to see her.

However, her persistence paid off. “I felt terrible going up to this great champion and saying, ‘They suggest that you don’t play,’” said former LPGA vice president Barbara Romack. “But I told her that they wanted her to play next year. She said, ‘I understand. I don’t want to cause any trouble. I just want to play golf.’ She did not play that year, but the following year, she played in both tournaments, and the tournament chairmen each invited her to stay in their homes, which she did.”

Despite her undeniable athletic ability, Gibson never secured a professional golf tournament victory. Her best finish was a tie for second after a three-way playoff at the 1970 Len Immke Buick Open.

After retiring from competitive sports, Gibson continued to break barriers. In 1975, she was appointed New Jersey’s Commissioner of Athletics, a role that provided much-needed financial stability. However, her later years were marked by health struggles and financial difficulties. She declined interviews, preferring to live in quiet dignity, until her passing in 2003 at the age of 76.

Yet, Gibson’s legacy speaks volumes today. Her achievements paved the way for future athletes of color, and she often credited those who supported her along the way, believing that success is never a solo journey. As she once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.”

The City of Springfield has long taken great pride in its two municipal golf courses — Franconia Golf Course and Veterans Memorial Golf Course. In recent years, the city invested $1 million to renovate both courses. Veterans has since hosted multiple qualifiers for USGA and Mass Golf events, including the 2023 U.S. Junior Amateur and U.S. Girls’ Junior Amateur.

But you can’t tell the whole story of golf in Springfield without reflecting on the history of the Home City Golf Club, Springfield’s first Black golf association, and Joe Perry (depicted in graphic atop this page), one of its earliest leaders and standout golfers.

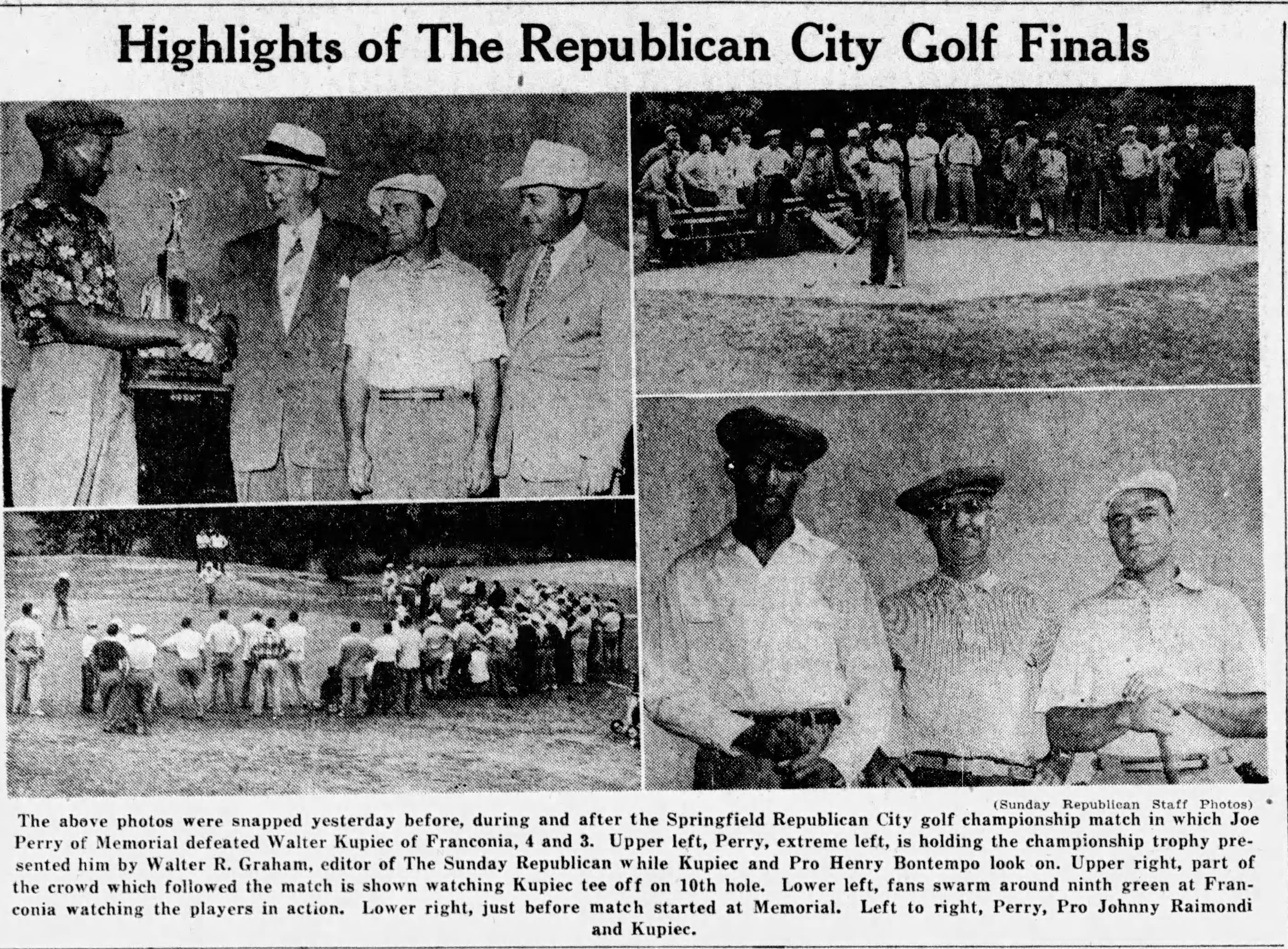

In 1953, Perry broke through the city’s biggest golf stage, winning the Springfield Republican City Open — the first Black golfer to do so. His 4&3 victory over Walter Kupiec at Franconia was witnessed by dozens gathered as Perry claimed the trophy, etching his name in history.

A dominant force in local golf, Perry’s achievements didn’t stop there. In July 1964, shortly after the Geoffrey Cornish layout at Veterans debuted, Perry shot a course-record 63 at Veterans, carding four birdies on the front, three on the back, and an eagle on the 14th — shaving four strokes off the previous record.

That same year, he teamed with Bob Bontempo to win the inaugural pro-member tournament at Veterans. Despite their victory, the soft-spoken Perry — often his own harshest critic — called it a “hacker’s round” for shooting a 73 at his home course. “This was one of my bad days,” he told reporters. “After all, this is my home course. I should never go over par.”

He played in the 1963 Massachusetts Open at Kernwood Country Club and, in 1966, claimed victory at the Home City Western Mass Open with a two-under 70 at Veterans.

Perry wasn’t just a champion — he was a bridge between Springfield’s Black golf community and the broader game. In the 1960s, Perry offered a 10-week course for adults at Springfield’s Dunbar Community Center, which had a golf setup designed by Leroy Clayborne. Clayborne, who served as the city’s Park Commissioner from 1963-1969, also once led Home City Golf Club. Like many in the association, he had a military background, receiving a Purple Heart while serving in the Army during World War II, and, upon returning home, became a scratch golfer.

Perry helped bring Black golfer leaders like Charlie Sifford — the first Black golfer to break the PGA Tour’s color barrier — to Springfield for the Home City Open. Sifford’s presence was a glimpse of what was possible, as well as to bolster camaraderie in a sport that was steadily growing among Black men nationwide.

By 1968, Home City honored Perry’s legacy with the first annual Joe Perry Amateur Open, celebrating the 15th anniversary of his historic city championship win. The event, which awarded $500 in trophies and prizes, included a nine-hole exhibition featuring Perry himself. Amateurs who bested his front-nine score earned special recognition.

Years later, Perry’s place in Springfield golf remained unshaken. In 1989, Perry was recognized as the best Black golfer in Springfield history at the Best Black Golfer Tournament at Veterans. Though the day’s low scorer was Ed Smith with a 76, it was Perry who was most feted on that day.

Great fortune also found the Perry family later in life, as Perry and his wife Velma won a $2 million Massachusetts Megabucks in 1990 using family birthdates 13-14-23-25-26-27. Perry, 66 at the time, was able to quit his part-time job and said he looked forward to traveling and fixing up their home and, of course, having more time and resources to play golf.

For decades, Robert H. Hawkins’ contributions to golf history remained largely a footnote, seldom remembered in the game’s ever-evolving landscape. But today, his legacy is resurfacing. Thanks to the efforts of the organization Rediscover Mapledale, an initiative dedicated to preserving his story, Hawkins’ pioneering role in Black golf is finally receiving the recognition it deserves.

At a time when Black golfers were barred from many clubs and denied entry into the nation’s top tournaments, Hawkins carved out a sanctuary in Stow, Massachusetts—Mapledale Golf Club, one of the first Black-owned and operated country clubs in the United States. Born in Adams, MA, in 1889, Hawkins worked as a caddy in his youth before becoming a chef at various private clubs.

But Hawkins was ambitious and, in 1926, purchased the 196-acre Randall Estate in Stow, transforming it into Mapledale Golf Club — not just a golf course but a full-scale country club featuring a nine-hole course, horseback riding, and tennis facilities. It quickly became a summer retreat for Black professionals seeking a place to play without restrictions.

Just a year before Mapledale officially opened, another historic moment was unfolding. In 1925, Hawkins joined a coalition of Black golfers and club owners in Washington, D.C., to form the United States Colored Golf Association (renamed the UGA in 1929), a national body that would provide Black golfers with the competitive opportunities denied to them in the white-dominated sport. While the idea of a national organization had circulated for years, historians credit Hawkins as one of the key voices who pushed for its creation.

In 1926, Mapledale hosted the first-ever national championship for Black golfers. Harry Jackson emerged victorious in a 72-hole, two-day tournament that would set the stage for the future of Black golf. The event was open to any golfer who could pay the $4 entry fee.

“We knew what it was like to be excluded, and we didn’t want to do the same to anybody else,” said tournament chairman Norris Horton at the time.

Dr. George Adams and Dr. Albert Harris, two Black physicians from Washington, D.C., were among those who traveled to Mapledale to play. They became instrumental in organizing the event, ensuring it was a success. Over the next two years, Mapledale continued to host the national championship, with Pat Ball winning in 1927 and John Shippen, the first Black golfer to compete in the U.S. Open, claiming victory in 1928.

Over the ensuing decades, the UGA continued to evolve into a proving ground for the best Black golfers in the country. Such individuals included the likes of Ted Rhodes, Charlie Sifford, Renee Powell, and Lee Elder, all pioneers who would later break through professional golf’s racial barriers.

Despite the profound impact of the UGA, both the organization and Hawkins’ contributions faded over time. The PGA of America’s infamous “Caucasian-only” clause, which explicitly barred non-white players, remained in place until 1961. As Black golfers gained increased access to previously segregated tournaments, the UGA ceased operations in 1976 but was reestablished around the turn of the century by Tarek DeLavallade and Andy Walker to continue the legacy of diversifying the golfing world.

Long before that, the Great Depression took its toll on Hawkins and Mapledale. Financial hardship forced him to sell the club in 1929, and it was renamed Stow Golf and Country Club. Today, the property still operates as Stow Acres Country Club, but Hawkins’ pioneering role was largely forgotten. When he passed away in 1973, his obituary made no mention of his role in founding one of the earliest Black country clubs in the nation or his contributions to the UGA.

That is now beginning to change. Rediscover Mapledale, an organization dedicated to preserving Hawkins’ legacy, has been working to bring his story back to light. Placards and signage now honor Mapledale’s role in Massachusetts golf history, and last summer, the group hosted a golf tournament to raise awareness as the 100th anniversary of the first UGA tournament approaches.

“This was happening at a time when professional sports were segregated, and access to the sport was limited,” said Stacen Goldman, co-chair of Rediscover Mapledale. “No matter whether you’re Black or white, no matter where you come from, you should be thankful that people were able to do this—to create a richer, fuller, and better history of America than you might think.”

As part of Black History Month, Mass Golf will pay tribute to the stories, achievements, and legacies of African Americans who demonstrated their mastery of the game and dedicated their lives to make it a pursuit for all to enjoy. #MassGolf | #BHM pic.twitter.com/ccNiGg5BR1

— Mass Golf (@PlayMassGolf) February 1, 2024