By Steve Derderian

sderderian@massgolf.org

–August 23, 2024-

Just about every golfer who has played the game has questioned their future within it. With every obstacle thrown his way, Charlie Owens absolutely faced his own doubts and was met with cynics. But golf in the 1970s & 80s was undergoing transformations in fashion, equipment, and the way the game was played. Emphasis on that last part, as Owens strayed from traditional norms, opting for a playing style that felt most comfortable and would overcome his physical limitations.

Owens, the son of a greenskeeper at the municipal course in Winter Haven, Florida, was self-taught and had a home-made swing like so many fellow African American greats. Calvin Peete played with a bent left arm, and Lee Elder had a double-overlapping grip. From the moment Owens picked up a golf club until his last-ever round, he used the same unorthodox cross-handed grip.

More noticeably, he played with a severe limp as the result of an injury from a paratrooper training exercise back in the 1950s. His left kneecap was removed, and his femur and tibia were permanently fused together. He also had arthritis in his other knee and spurs in his ankle. To top it off, he later developed iritis in one eye, which made his vision blurry, requiring eye drops and special sunglasses. And, of course, he grew up in an era of segregation, particularly in golf. But that began to crumble following the PGA of America’s 1961 decision to lift its “Caucasian-only clause.”

Following his honorable discharge from the U.S. Army, Owens picked up the game again and decided to join the ranks of the first generation of minority players eligible to compete in top-tier tour events.

Today, many consider him to be one of golf’s most overlooked pioneers. In addition to his playing style, he championed new equipment as well as cart policies to help talented golfers who faced disabilities not related to the game (more on that later.)

Before that, he was a 37-year-old journeyman seeking a paycheck when he drove from a Monday tour qualifier in New York to a motel outside Boston in the steamy summer of August 1974. Owens won the 1971 Kemper Asheville Open and earned his tour card in 1972, but an ankle injury kept him off tour for 11 months starting in 1973. By April 1974, he was back to the life of Monday qualifiers and other random opportunities to earn his way back to prominence.

By that time, the United Golfers’ Association was on the doorstep of 50 years. The association, which held its first championship in 1926 at Mapledale Country Club (now Stow Acres), had provided much-needed opportunities to showcase and reward African American golfers nationwide, particularly through its national championship. The event, which funded scholarships for deserving area black students, was slated for Braintree Municipal Golf Course that year, and marked the final time it was held in Massachusetts. Owens knew of this event through Lee Elder, a five-time winner who was the first Black man to play in the Masters.

“I want to win this,” Owens said before the final round. “I told reporters in Florida I felt this way before the Florida Open. No black had ever won it. I became the first. This is the same way. It’s supposed to be the best black tournament and it’s the only black tournament I’ve never won.”

That changed on August 23, 1974, when Owens shot 72 in the fourth and final round to notch the win and the $2,000 prize to go with it.

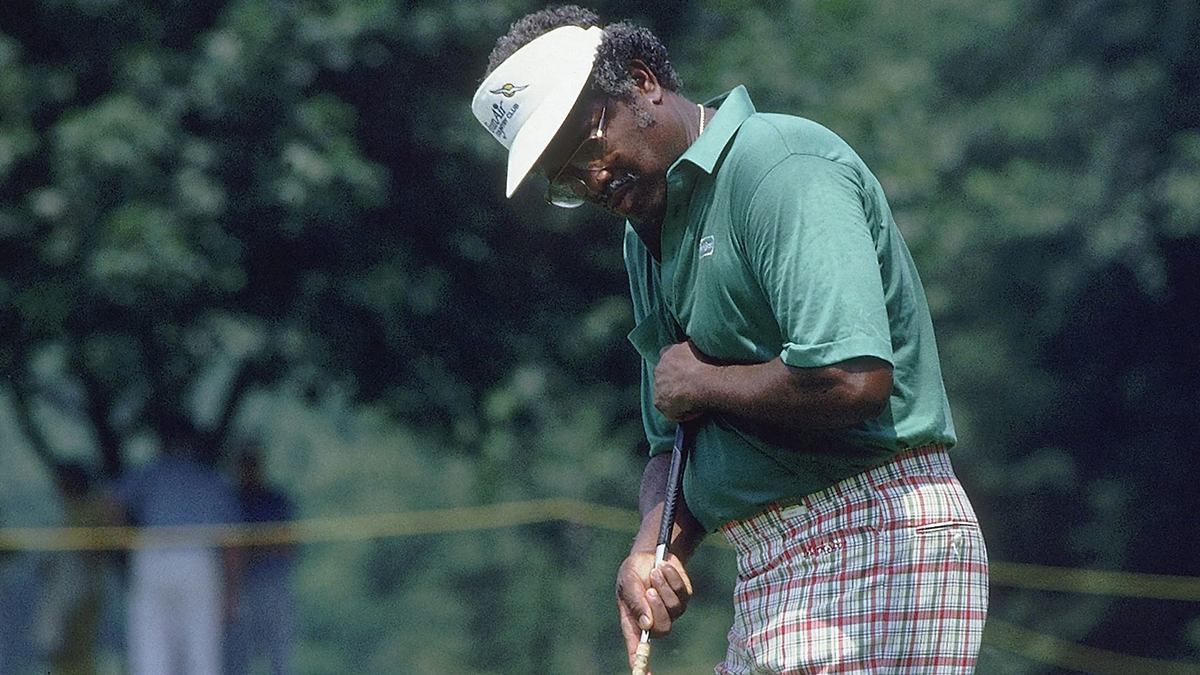

Despite all his physical disabilities, onlookers marveled at the cigar-chomping, mustache-sporting Owens, who struck the ball with incredible precision, limped his way to his ball, and then did it again. While he was known to hit 300-yard drives with nearly outdated persimmon clubs, he often used a wood or 1-iron to place his ball around Braintree’s tree-lined course with rough and water hazards lurking throughout.

That consistency suited him well. He shot 70 in the first two rounds to open up a sizable lead. That narrowed when young Georgia pro Bobby Stroble smashed the course record with a 66, while Owens said he was too relaxed early in round three, making bogey on three of his first six holes, only to rally with five birdies to take a four-shot lead to the final round. While tempted to use it more, he hit the driver just once in round four, landing in the rough on the 6th and later saying, “I let my driver go back to sleep.”

He later reflected on the sheer will it had taken him just to be out there playing. “I’ve had my physical problems for 13 years,” Owens said. “If people only knew the pain, the antagonizing aggravation I’ve gone through.”

Owens made about half of his cuts in 47 events on the PGA Tour, but when he reached the senior tour in 1983, he received the ability to play out of a cart. He won twice in 1986, earning him a spot in the 1987 U.S. Senior Open. However, the USGA did not permit carts for its premier senior championship. In an act of protest, Owen took to the course with crutches, dropping them between shots and slowly negotiating the swerving and hilly terrain. He withdrew after shooting 77 in Round 1, addressing reporters with a simple request that carts be allowed next year for individuals who need them to play. Today, the policy for USGA Championships reads: “…consistent with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a disabled player or caddie may be permitted to use a golf cart as an accommodation to his or her disability for those events where golf carts are not allowed.”

“It’s like putting a rope with a 100-pound weight on it between your legs and then trying to walk,” Owens explained. “We’re all over 50. And one of us is handicapped. Me. I want to compete, I want to win, but I can’t even play because I can’t walk. Believe me, if I could walk, I would. I just don’t think it’s fair.”

During that time, Owens also turned heads with another game-changing device — a 52-inch putter, with his left hand held to his chest and his other swinging freely. He crafted the design himself before taking it to a machinist friend, creating a club that Owens himself described as a “flying saucer with a square face. That thing was so ugly.”

I imagine what you might be thinking: Owens’ use of such a putter wouldn’t fly today. But in 1989, the same USGA that was bullish on its cart policy two years prior declared that long putters were “not detrimental to the game. In fact, they may enable some people to play who may not otherwise be able to do so.”

The impact was immediate as Orville Moody won the 1989 U.S. Senior Open with a similar putter, and two years later, Rocco Mediate became the first to win on the PGA Tour with a long putter.

At age 76, Owens published his biography I Hate To Lose: How a little-known, handicapped black man beat the best of the best on the PGA Tour. He describes his journey from hitting bottle caps with tree branches to his later years, all with faith intertwined in everything he did. Even in his 70s, with crotchety legs and poor vision, he couldn’t resist a game with friends, even if they tried to tire out the former pro.

Owens died nearly seven years ago, but his story remains one of perseverance, excellence, and the unyielding belief that the game of golf belongs to everyone.

“When my time comes, I hope they’ll all find me on the 18th green with that big heavy, long putter in my hand — passed away peacefully, doing what I loved,” Owens included in his book. “In fact, they can put that on my tombstone.”

Mass Golf is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization that is dedicated to advancing golf in Massachusetts by building an engaged and inclusive community around the sport.

With a community made up of over 130,000 golf enthusiasts and over 360 member clubs, Mass Golf is one of the largest state golf associations in the country. Members enjoy the benefits of handicapping, engaging golf content, course rating and scoring services along with the opportunity to compete in an array of events for golfers of all ages and abilities.

At the forefront of junior development, Mass Golf is proud to offer programming to youth in the state through First Tee Massachusetts and subsidized rounds of golf by way of Youth on Course.